Transcript

So I’m working on my next book, or I should say it’s working on me. I’m still in the early stages, where I’m writing toward the book more than writing the book itself—keeping a journal, doing research, musing about themes, hazarding some guesses. It’s all the stuff that comes at the beginning, before you know what the book is about, and it’s a time of hope and excitement and occasional glimpses, but mostly it’s just a time of patience and pure puzzlement. It’s not at all clear how the various strands will come together—of if they will—and no clue at all how long it will take. It’s an absolutely critical stage of writing, and it takes as long as it takes. I’m coming up on the three-year anniversary of this one.

So after three whole years of writing toward this book, just imagine how excited I got recently when the overall shape of the book started to come clear. I caught a glimpse of a through-line, a deeper theme tying it all together. I was thrilled! At last I’d be able to dig in to the chapters themselves!

So I opened up a chapter file and got to work. A decent beginning, lots of notes about where to go next. And then it just . . . fizzled. Things got murky, like somebody had dumped a ton of sediment into my clear water. I couldn’t make any headway at all.

So I closed that file and started working on a different chapter—only to find the same thing happening again. Getting bogged down almost as soon as I started.

Right about then a new writer-editor friend on Substack published a post about the mysteries and magic in the writing process—thank you, Amanda Hinton! She closed her post with a question: “How do you relate with the unknowns of writing?”

And somehow that question forged itself into a tiny key that sought out a tiny lock inside me, and suddenly the door swung open. I knew why I was having trouble writing this book.

It goes back to the process I followed in the first two books. When I sat down to write the first one I was in my forties, a longtime editor. I’d helped to shape and polish literally hundreds of books for other people over the past twenty years, but this was the first time I’d sat down to create a book myself. I had no idea what I was doing.

It was a fertile place—writing to find out what wanted to be written, writing without a plan. Sure, I had a book proposal and a table of contents and chapter summaries, but these were mere suggestions. From working with so many other authors, I knew that in the writing process surprises always happen. Outlines shift. And sitting down to put words on paper is the only true test for finding out what really belongs in a book.

So I sat down, and I wrote. I had a story to open and close each chapter, like bookends, but I had no idea what belonged in all those middles. So in each chapter I followed thoughts and images as they showed up in my mind. I mused aloud on the page. And I paid attention to anything that crossed my desk that arrived with a little zing. You know the feeling—something catches your attention a little more than usual, suggests it might have something to say to you. Each time something captured my attention, I made a note of it. I asked whether this thing could fit into what I was writing. More often than not, it could. By about the third chapter I realized that anything that crossed my desk with that little zing wanted to be woven in to the chapter at hand. So I worked it in.

And that became my method for the whole book: starting with a few vague ideas for a chapter, then plowing through each chapter according to what thoughts idly crossed my mind and what snippets of other people’s essays or poems or commentary fell onto my desk. It was a magical process, an intuitive process, full of hope and possibility and meaningful coincidences. Somehow the perfect ingredients for that chapter would arrive in my writing kitchen at just the right moment, and all I had to do was to wash them up and chop them and toss them in the stewpot.

It was a path of listening. And it was possible because I didn’t know what I was doing. I was in beginner’s mind—out of necessity. I’d never written a book before, so I was open to what might want to appear.

So the first book got published, and some years later, when I felt an urge to write a second one, I started again with a story. At the time I thought the story belonged in the introduction—that this story needed to come first so that readers would understand the rest of the book. But as I wrote this story, it grew and grew, and soon I realized I was writing the book. This was what the book wanted to become.

So, clearly, again I was clueless—no idea at all what the real book was about. Beginner’s mind all over again. I simply wrote what wanted to be written, listening to those inner urges, following my nose. And it became a book.

Now I sit down to write the third book. It’s been twenty years since that summer day in my forties when a flash of inspiration started me on the first one. So many things have changed! I understand more about who I am—and therefore what each book is about. I’m old enough to see the strands and the threads begin to weave themselves together. It’s a stunning process, to watch the threads of your life braid themselves into some kind of beautiful sense. I get to do this because I’ve been given a long-enough life to witness it. What astounding good fortune!

My younger self still sometimes stares, unbelieving, that the seemingly unrelated things she wrestled with so hard in earlier years could ever flow into a semblance of order. As if all those varied streams were gathering in secret that whole time, plotting to come together. And as if I can now see the whole landscape—where they began, as rivulets, far upstream, and how they meandered closer and closer, finding their way into one flowing river.

It’s an enviable position I’m in now, twenty years later. I know what I need to write. And now I even know what wants to be in this book. What a thrill to have lived long enough to arrive at this place! At last, against all odds, I have a pretty good idea of what I’m doing!

But guess what? Knowing what you’re doing may be thrilling in life, but it’s no good for creative writing. In fact, it’s a disaster for the writing. Because writing, to sing, needs that freshness that comes from an open heart. From a beginner’s mind. When we know too much about what we’re doing, it’s tempting to trust all those good ideas from the mind instead of opening to something larger, something just out of sight, something that wants to be teased into view. When we know what we’re doing, we quit trusting the heart.

And that’s where I’ve been tripping myself up lately. I know too much about what I’m doing. I’ve gotten too smart for the writing. It’s like I put on these big heavy shoes, ready to take on the world. And instead, what this book needs is the heart of a child, ready to lose herself with awe in the next miracle coming into view. Ready to spend the next eternity of moments staring at a flower or a bug, transfixed. Ready to be brought up short by wonder.

So it’s time to kick off those oversize shoes and toddle through the grass again in my bare baby feet. Time to forget all the outlines and start from an open heart. Time to become a beginner again. To listen for what wants to be written. And when I do, the path opens up, like magic. It opens by listening.

I shouldn’t be surprised that listening is what opens the path. It seems to be what life has been trying to teach me for a very long time.

Some years ago I ran across a poem by the Indian poet and writer Kailash Vajpeyi. It’s a short poem of seven lines, and the last four of those lines read like this:

Since drowning is inevitable

Never trust the boat

But do

Trust the river.

I’m in awe of the poet’s vision. He saw so clearly just how flimsy all our boats are against the power of the river. How the craft we build so carefully cannot carry us through.

There’s something awe-full too, in the sense of terrible and wonderful at the same time, in his ambiguous image of the river. “Since drowning is inevitable”: we will land in the water sooner or later, he says. The river will drown us; we can trust it to do that. But there’s a double meaning here, because the river is also what can be trusted when our own craft gives way. The river is also what saves us: “Never trust the boat / But do / Trust the river.”

Trusting the river is advice I wish I had heard a lot earlier in life. When I was a young adult, the go-to advice was to set goals and make a plan. Get your education, dig into work, have a family. Calculate the next career move, the next relationship move: is it lateral, or is it up? The point is always to go up. And think ahead. Save for retirement. Choose your goals and work toward them step by step.

The poem reminds me that in my twenties I tried all of this. I worked so hard to fit in, to find my own foothold in life! I got married, I went to grad school, I cultivated friendships, I built a résumé. And, friends, I was so conscious about it all too—I learned to meditate as well! I might have been prepared for just about anything.

But life has a way of poking holes in even the strongest boats. An accident, an illness, a death or divorce, and our boat begins to leak. Water starts to seep in, more and more water, because water can always find a way.

It was illness that ripped the first gash in my boat. In my early thirties I came down with a bad flu, the one making the rounds that winter in the Bay Area, where I was living. My fever rose and rose, topping out finally at 104.5 degrees. I called it my KFOG fever, after the biggest rock station in the area, at 104.5 FM. The fever came with a backache so severe that one night I couldn’t lie in bed at all but had to kneel beside the bed with my stomach and hips resting on the mattress just to catch a few hours of sleep.

But even after the fever broke, I didn’t get better. Crushing fatigue kept me in bed. My brain turned fuzzy. I couldn’t think straight. Fluorescent lights made me dizzy and sick. And worst of all, I couldn’t read anymore, which is a real problem when you’re a doctoral student taking comprehensive exams and paying tuition every semester.

My heart goes out to people now with Long Covid because I understand just how much damage a virus can do. I spent four long years recovering from that one. While my student peers were graduating and moving away, I was lying down and napping, morning and afternoon, working my way slowly out of bed, getting better in fits and starts, two steps forward, two steps back. I had to let go of all my life plans. I learned to move at the pace of a snail, taking each day as it came, no expectations. I lay on a bench in the backyard and stared at trees. I began talking to trees. I watched the sky. I breathed. And gradually, over months and then years, I recovered.

But even though my body was mending, my boat was still listing. Two years into my recovery my marriage ended and both of my parents died, all in the same year.

And that was it for my boat. It went completely under. All that work I’d done, all those great preparations I’d made—none of it could hold me. I sank down, down, into the depths, claimed by depression for the next several years.

I have this to say about drowning: there’s no fun part of it. And this too: the more faith we have put in our boat, the more shocked we will be when it sinks out of sight and cold water rushes against our skin.

Life forced me out of my boat and into the river. Life let me drown.

And I don’t know how, I can never explain it, but life also picked me up and held me at the same time. The river that drowned me was the same one that carried me. Kept me going, teaching me bit by bit how to surface for air, how to ride the currents. And teaching me, most of all, to hold my plans and my ideas and my goals more lightly. When I surfaced again for good, I was a different person—more ready to let my heart lead, more ready to trust the flows of life to carry me home.

So when I talk about a path of listening, I mean this: being willing not to know what comes next. Being ready to lay aside all the worthy goals and the thoughtful outlines if, in that tiny place inside the heart, we hear a different music—a sweeter music—calling. It means turning to follow those sweeter tones even if they lead us away from the security or the destination we thought we wanted.

And it means developing a posture of listening in everyday life. Proceeding by feeling and by instinct more than by plans. Coming to the end of an activity and pausing for just a second or two to ask, “What wants to happen now? What might be helpful next?” And then moving in that direction, even if it departs from the program.

It’s a more humble way to live because we’re responding to what is needed in the moment. By pausing for a few seconds to listen, we acknowledge that there are other players in the world—not just humans but trees and clouds and oceans and whales—and we move in response to how they are moving. It’s less of a “master of the universe” approach and more of a cooperative spirit, like, “Let’s go forward together, okay?”

In my experience it takes a long, long time to get used to this way of moving. Illness in my thirties was my initiation; it forced me to learn how to move slowly and listen for the next opening. So I probably have that illness to thank for the fact that, years later when it came time for me to write a book, I was willing to allow the process of writing to unfold in an organic, moment-to-moment way.

But even after decades of practice, I still forget so easily. I still grab for the mental constructs. I still try to impose my own expectations on what is coming to be. And after writing two books by listening from the heart, I just recently forgot again and began to trust my chapter outlines instead. I aimed the writing toward that brilliant conclusion I thought I wanted instead of just listening. Just allowing the wonder, and the gift, of a moment-to-moment unfolding.

There’s a poem that has accompanied me for decades. It’s “The Waking” by Theodore Roethke, and it opens with these lines:

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I feel my fate in what I cannot fear.

I learn by going where I have to go.

Three simple lines in that first stanza, and they give us enough to work with for a lifetime! But the poet keeps going:

We think by feeling. What is there to know?

I hear my being dance from ear to ear.

I wake to sleep and take my waking slow.

There are four more stanzas to this magnificent poem, each of them a genius in its own right, and they’ve all been great company to me over the years. They help me remember to just keep listening for that irrepressible dance of being.

So, I am hoping for each of us a heart that is open to listening and some bravery to trust what unfolds. And may your own being dance from ear to ear.

For digging deeper

Check out Amanda B. Hinton’s post, “Your Inner Magician (And Other Mid-Move Thoughts),” July 6, 2023, at The Editing Spectrum on Substack.

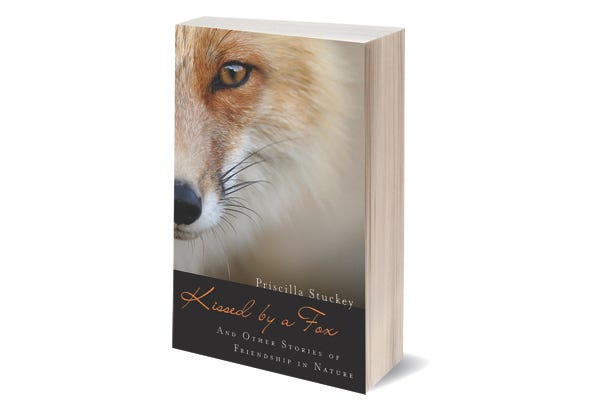

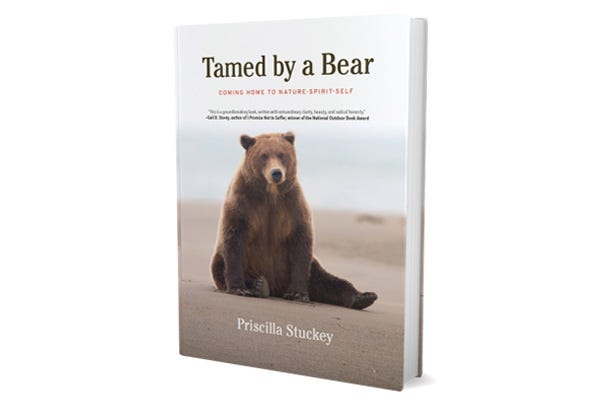

I discovered the work of Kailash Vajpeyi through his daughter, the writer and scholar Ananya Vajpeyi, who wrote a moving essay about performing the funeral rites for her father after he died. She quoted the poem, which she translated from the Hindi, in that essay. The essay originally appeared in the LA Review of Books, and it was excerpted at On Being, and that excerpt is what I found: “The Incessant Flux of Life and Time,” November 17, 2015. I was so taken with the poem that I located Ananya at her university in India and emailed her, asking for permission to use the poem as the book epigraph for Tamed by a Bear, and was thrilled when she said yes.

You can find Theodore Roethke’s poem “The Waking” at the Poetry Foundation.

Share this post