So last year, in my mid-sixties, I discovered that I’m autistic. But what took me by surprise wasn’t the diagnosis, it was the overwhelming feeling of relief. Why so much relief? We talk about that today—how I, like many people, held an extremely narrow view of autism; how autism consists not of one spectrum but of eight or ten different ones; and how each autistic person is their own colorful configuration of things in life that may be harder for them and things that may be easier. I muse on how being autistic (without knowing it) led me early in life toward meditation and toward connecting with nature, and how it laid the foundation for working today in nature spirituality. We talk about some common misconceptions of autism, and I reflect on my work life as an autistic person. We also review what slime mold taught ecologists about loners and outliers. Finally, we celebrate the radiance of an Earth that, in Darwin’s elegant words, has brought forth “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful.”

Transcript

So about a year ago I learned something new about myself. I began to suspect that I’m autistic. So I approached a psychologist, and we had some meetings, and I took some tests. And when the meetings were done and the scores came back, the answer was yes. I’m autistic.

Now as you can imagine, it’s possible to have a lot of different feelings about this. But what took me by surprise was the very biggest feeling, which was also the first one. I felt relief. Huge relief. As if I could finally relax now. Especially in those hidden, tucked-away parts of myself, I could relax.

Things made sense now. Things that I’d wondered about my whole life, things I had tripped over now and then over the years, like old toys or books littering the floor, had a place now. Like someone had built me a whole new organizing system, and finally there was room for everything. Nothing left out. I could pick those last pieces up and tuck them away. My room was spacious now. And free.

So it’s pretty unusual to get diagnosed in your sixties. Why did I wait? Well, I didn’t. It’s just that being autistic never occurred to me. And it didn’t occur to me because I held the common view of autism, which is extremely narrow.

When I heard the word autism I remembered the little nonspeaking girl I knew years ago who couldn’t make eye contact or get hugs. I didn’t know that highly verbal people can be autistic too. And that nonspeaking people may be high academic achievers. This past week a nonspeaking autistic woman delivered the valedictory address at a college in Florida. Autistic people might look shy or outgoing. We might seek adventure, or we might avoid it. We might be messy or super organized. Being autistic just means that a person processes the world differently than most people—we may do some things more easily, while other things may be impossible for us or take more time and effort.

The common idea is that there’s one autism spectrum, with traits running along a single line from “less autistic” to “more autistic.” But this can’t begin to describe the variations among autistic people. As the saying goes, “If you’ve met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person.”

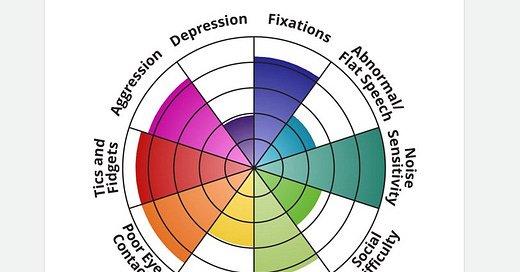

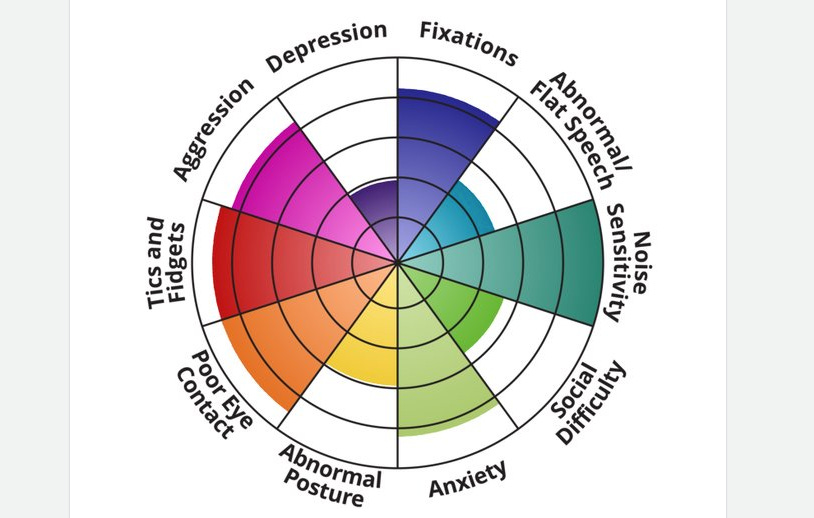

A much better way to picture autism is in a big bright circle like a pie chart, with each piece of the pie a different trait and a different color of the rainbow. And each of those eight or ten different pieces of the pie has its own scale, its own spectrum. So there’s not one autistic spectrum; there may be eight or ten different ones spread around a circle, with each autistic person having their own colorful configuration of traits. For each of us, different things are easier while others are harder.

So I thought I might talk a little today about what some of those easier and harder things are for me. And why, because of those traits, learning that I was autistic came as such a relief. I also want to talk about how my experience of being autistic connects with what I do in the world, namely, write and teach and mentor people in the spirituality of nature.

So let’s start with something that’s hard for me. Over my lifetime, one consistent feeling is the feeling of being different. And whew! This is a big one. When I was a kid it was overwhelming to feel so different from all the other kids. I always identified with the adult in the room, and I had no idea how to talk with other children. I’ve heard one autistic person say that to him, other children might have been another species, like ducks. In gradeschool he would think, “Wow, look at these funny little creatures. Aren’t they cute?” I’m afraid I understand what he’s talking about! Though throughout school I did always have one or two friends I could be myself with, and I always enjoyed spending time with them one-on-one.

Feeling different was something that eased a lot over time. I grew up, I went to college, I moved to the big city, and I lived in Oakland, California, for twenty years. And the farther along I moved in life, the more room there was to be me. More friends, more people for company. I forgot about feeling different; everyone was different!

But I still got feedback from time to time that I wasn’t like everyone else. In my twenties, my closest relatives thought I was crazy. Even in later years the judgment would come now and then: I was too serious or too intense or too emotional or too sensitive or too blunt or too quiet. Just too much of something or other.

Now, years later, I understand that these are the kinds of reactions autistic people often get from others. And I have a request to make: Let’s not do it to each other, okay? It’s hurtful. It leads some people to set themselves up as better than others. And for those on the receiving end, it leads them to question and doubt themselves, to wonder what’s wrong with them. I’ve sat on both sides of this judgment, and I know from experience: nobody can make their best magic in the world when they’re feeling either superior or self-doubting. Being a human being, especially a wise and decent human being, is a complicated thing, and there are endless ways to do it well, including endless autistic ways. When it comes to differences among us, we don’t need judgments, we need openness: being willing to learn and understand and accept.

So I mentioned before that once I moved to the big city, being different wasn’t an issue anymore, because everyone was different. Well, that was only partly true. What I did was, I learned over time how to make accommodations for myself so that I could live as happy a life as possible—but they were accommodations that tended to separate me from others, out of necessity.

Because one of the things that’s really hard for me is being social. I have always needed alone time. A lot of alone time. So much alone time that I could never work in an office setting, even if I enjoyed the type of work or the people in the office. I needed quiet, I needed independence, and I needed to organize my own time. And I needed all those things so desperately that I was willing to give up financial stability to get them.

So in my late twenties I found I was good at editing—it’s true of many autistic people, that we can spot details that others miss—and I made a thirty-year career of editing. But to be comfortable at work I had to be a freelancer, and this meant cobbling together an income however I could, living month-to-month during most of my adult life, and never having the benefits of a regular or full-time salary. Living that way can be stressful, and it often was.

But even there I was fortunate. Because, among autistic adults, even college-educated ones, 80 percent of us are unemployed or underemployed. That means 4 out of 5 of us are not working at all or are radically overqualified for our jobs. Only 1 out of 5 of us finds work that suits us. So even here I’ve been one of the lucky ones.

And living on the edge financially has made a difference in my value system, which is where we start to come around to nature spirituality. I began connecting with nature long ago partly because it didn’t cost much. No cover charge to visit a local park or hike beside the ocean or watch birds! So I began doing all those things as a grad student partly because they were the only things I could afford to do regularly.

And because I was spending time in nature partly because of thin pockets, it opened my eyes to just how precarious living on Earth is for all beings. Every animal depends for its life on the food that becomes available in its world day by day. Every being lives on the edge, only a few hours or a few days away from death by starvation. Even those who stockpile food, like woodpeckers, are completely dependent on the health of the trees that produce their nuts, and forest health depends on the right amount of moisture and sunlight—all of which can change from month to month and year to year. Especially if something like climate change messes with the patterns.

Seeing the precarity of all life opened my eyes to just how horrendous it is for human beings to interfere with the patterns of weather and climate and habitat that all other beings rely on to survive. These are sacred patterns, worked out over millennia by the birds and the bugs and flowers and trees and microbes of a region. And yet now we are changing them faster than those beings can adjust to. Being a good human means every one of us doing everything we can to slow climate change—in our individual lives as well as in our shared systems.

When it comes to being social, there’s the issue of eye contact. I actually remember the moment when I was maybe ten or twelve years old, and I decided that looking in people’s eyes felt too intense for some reason, so I would look instead at their noses or their teeth, which is what I’ve done ever since.

Or there’s the matter of going to parties. I always looked forward to a party, because I love to connect with people, and I love being part of a community. And at a party I may even look like I’m having fun, for the same reasons. But I’m working really, really hard to do it. I pay a huge price just to be in a room with that many people. And when I leave, it will take me a long time—maybe as much as a couple of days—to recover my equilibrium, to feel like myself again. A party can give me an excited buzz, but it’s a stressful buzz at the same time. Social contact, for me, is exhausting. I pay a big price for it.

And here’s one way that thinking “everyone is different” didn’t serve me very well. It led me to downplay the particular ways that I was and am different, such as needing a lot of recovery time after being social. I did learn how to give myself that time, but I’ve always done it sort of grudgingly, always feeling impatient about my limits rather than just accepting them and being generous toward myself about them.

So I have another request to make: let’s not do this to ourselves, okay? Life is hard enough without fussing at ourselves for how we were born—whether it’s how we look or how we process experiences or whatever it might be. Acceptance starts at home, and when we can increase compassion toward ourselves, we set a playing field of kindness in the world around us. Everyone is different, yes—and that’s not permission to downplay our own needs; it’s permission instead to respect them fully.

So through my thirties and forties and fifties I became really good at blending in with others. For autistic people, this is called masking or camouflaging. We often have to hide parts of ourselves because they make other people uncomfortable. For me, masking has often been less about hiding who I was than about just leaving parts of myself out in a social setting because I’d learned they were parts of me that other people might not be able to relate to. Leaving them in the background was just the easiest way to connect with others.

I trained myself to meet other people on their own turf, so to speak. I might communicate in the mood or the style that was comfortable for them, or I might talk with them about the interests that they enjoyed. If you’re doing this constantly, it’s hard work. But whenever I’ve found someone who returned the favor, it’s always a huge delight, and that’s when a friendship can deepen.

So, this brings up the idea of empathy. A common misconception of autism is that autistic people lack empathy or are unable to feel it. But empathy is just one of those eight or ten traits in the big circle, and people can appear at different points on this scale as well. Some autistic people are actually hyperempathetic, easily able to pick up on the feelings and needs of others.

And in the right setting this can be an enormous asset. The job of editing someone else’s words, for example, requires a great deal of empathy. Many editors talk about how they try to “get inside the head” of the author. It takes just that kind of close attention and empathy to bring out what an author means to say. And some of my most satisfying editing relationships have been those where I could work closely one-on-one with the author, which was always a big help in getting inside their head.

Meeting others where they’re at was also a great skill to have while I was mentoring graduate students. My second career, in addition to editing, turned out to be teaching humanities in a nontraditional graduate program. For a decade I was mentoring students one-on-one, which to me was heaven. It was the perfect teaching structure for an autistic person!

One year I had two very different students, both in religious studies. Each of them was brilliant in their own way, but they needed what to me were obviously very different kinds of support. Eventually these two students found each other on campus and started comparing notes. And when it came to relating to their academic mentor, they had almost opposite experiences. So when they finally realized they were talking about the same person, they told me they were shocked. When I heard the story I laughed, of course, but to this day, it remains one of my proudest moments. Both of those students thrived in the program, both of them graduated, and both went on to teach afterward.

One of the autistic traits that has tripped me up over the years is sensory overload—how sensitive I am to noises and smells and changes. Motion and light can disorient me. And flares of emotion, like frustration, can suddenly take me by surprise and overwhelm me. I have experienced emotional meltdowns from time to time, which before my diagnosis were always puzzling to me.

So my internal landscape can feel pretty turbulent, which is what led me very early in life to meditation. Just out of college I took a yoga class—this was way back in 1980 in a small college town in the Midwest—and I got hooked on shavasana, the pose of the corpse. It’s the meditation of relaxing quietly on one’s back, giving oneself over to gravity, to the Earth. It turned out to be exactly what I needed to help modulate the stress and noise of everyday life. It helped to quiet that sense of jangling inside. And it has remained a foundation of my life in all the decades since.

Some have suggested that autistic people have a kind of direct line to spirituality, but I don’t see it like this. I prefer how the psychologist who gave me the diagnosis put it. She is also autistic, and when she found out I work in the area of spirituality, she said something like this: “Often life gives us the kinds of challenges that can make us proficient in spirituality.” That is true to my experience. I was curious about religion and spirituality from my earliest years, but the challenges of living as myself intensified my interest, made my need for spiritual connection more urgent.

Those challenges also led me directly toward connecting with nature, because nature never failed to soothe a jangled mind. Spending time in the woods or by the ocean gave me an experience of peace that seemed so elusive in daily life. Nature was a dependable refuge; I could count on it. Silent sturdy trees and gently twittering birds offered relief from the noisy, rushed, overstimulating world of human beings. Connecting with the lives in the forest or along the ocean never failed to put me in touch again with the bedrock of support that is the living Earth. And it always helped me dip again into my own inner wells of peace.

And now, in my sixties, I find that being autistic gives me a wonderful set of traits and experiences for working in nature spirituality. I am a kind of interpreter, lifting up the voices of water and land, bringing forward the wisdom of trees and birds and whales and bears. I am comfortable in the “between” places—between the human and more-than-human, between the seen and unseen. In my writing I am always trying to show how old ways of thinking do not have to hold us in thrall, that the dominant worldview is not the only one possible. I often find myself holding up a mirror to my own culture, and I am often making space for other kinds of wisdom, such as from Indigenous traditions.

Being autistic, in other words, has made me an independent thinker. Feeling different is powerful training in seeing differently, in imagining differently. Society needs the outliers, the visionaries, the ones who can see different and better ways of living.

I think of a study I read recently, a study in evolutionary biology done with slime mold. Now, slime mold is known for being intensely collaborative, hooking its cells together to reach into new places for food and resources. But researchers looking closely at slime mold noticed that during each collective project, not all of the cells joined in. Some of them always hung back. And those hanging-back cells were not flawed in any way; they weren’t just missing out on the action. The slime mold, as a community, was organizing itself so that some cells always sat out each project. The community was cultivating a constant percentage of loners.

And the researchers found that there’s a clear biological advantage for slime mold to have its loners. The cells that sit out a project become a kind of insurance policy, guaranteeing that if some disaster strikes the collective, such as infectious disease, not all of the slime mold will be wiped out. A few will remain to live another day. Evolution selects for loners too.

So everybody’s style is needed, among humans as well. Loners are valuable; unfettered imaginations are priceless. One autistic Twitter user, called Autistic Voices United, tweeted this week: “The way the autistic brain functions gives birth to revolutionaries in every field imaginable, endless forms most beautiful. We shake the foundations that new and better worlds may rise.”

I love that thought! And that phrase in the middle, “endless forms most beautiful,” is actually a quote from the very end of Charles Darwin’s book On the Origin of the Species. Darwin’s last sentence reads in part, “Whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved.”

Here’s toward a world where everyone gets the acceptance and support they need to bring out their own most beautiful and wonderful form. Because we’re stronger when we’re all different. We’re more resilient when we’re different. We need all the variations in human brains and human abilities. That’s how we survive. That’s how we can find our way together toward truly new worlds.

For digging deeper

Elizabeth Bonker, who became nonspeaking at fifteen months old, delivered the valedictory address at Rollins College using text-to-speech technology. See the “Raising Her Voice” story at the Rollins College site.

Looking at other little children as if they were a different species, like ducks, comes from Paul at “Are You Undiagnosed Autistic?”

For one example of the rainbow circle picture of autism traits, see the autism test at IDRlabs.com, available on their “Tests” page.

Claire Barnett talked about “Why Autistic Unemployment Is So High” in her TedX talk at Vanderbilt University.

Kate Kahle, in her TedX talk at Austin College called “Behind the Mask: Autism for Women and Girls,” explains why the label Asperger’s is not helpful and explores why autism is often missed in women and girls.

Science writer Steve Silberman is the author of Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity (2015). In the book he addresses myths about autism and outlines the twentieth-century history of the autism diagnosis. He talked about both in a wonderful interview in 2015 on Fresh Air with Terry Gross, called “‘Neurotribes’ Examines the History—and Myths—of the Autism Spectrum.”

For more on women and autism, see “Life on the Spectrum: Women Sharing Their Unique Experiences,” a panel of autistic women speaking at the MIND Institute at UC Davis in 2020.

The Autistic Self Advocacy Network is an organization run by and for autistic people. Their Resource Library page is packed with informational books, pamphlets, and toolkits written in simple, immediate language. See especially their introductory book, Welcome to the Autistic Community, for autistic people, parents, and allies, available for free under the “Books” tab on the Resource Library page.

A master list of helpful links comes from Amythest Schaber, who blogs at neurowonderful. See their videos at Ask an Autistic on YouTube.

For a sobering report on the challenges in health and housing that autistic adults and seniors can face, see “Growing Older with Autism” at the Spectrum News site. Much better social supports are needed so that autistic seniors don’t fall through the cracks of health and social care.

For the slime mold research from Princeton University, see “Loners Help Society Survive,” Science Daily, March 18, 2020.

Share this post