Transcript

You know that feeling when you’ve heard something so important you just have to share it? I have that feeling today. And it comes from watching a talk that Robin Wall Kimmerer gave last month in Montana. Most of you know who Robin is, a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, a professor and botanist, and the author of the luminous book Braiding Sweetgrass.

I was lucky enough to learn about this talk right away because one of the people I follow on Substack, a poet named Chris La Tray, wrote about it right after. Chris is an Indigenous Métis and a member of the Little Shell tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana. He’ s also Montana’s new Poet Laureate. And he wrote with such deep joy about Robin’s talk that I needed to go find it and watch it. And lucky I did, because it was online for only a few days.

So today is devoted to some highlights from the talk that Robin Wall Kimmerer gave at the University of Montana in October. She titled it “What Does the Earth Ask of Us?”

From the very opening of the evening I was moved. Chris La Tray introduced Robin by first thanking all the relatives in the room for being there—the human relatives. And then he called everyone’s attention to all the relatives outside the doors—the birds sitting on the wires and the deer in the woods. Long ago, his people say, the humans and the animals shared a common language. “I like to think,” he said, “that all of our other relatives still speak that language. They’re hopeful,” he said. “They want us to remember that language. They want us to remember what it’s like to be part of the wider world.”

And as I watch, the tears are springing to my eyes, because this is what I hope for every day of my life: for us to remember how to take our place as members of the Earth family. How to heal our broken relationships with land and water and animals, and how to heal our own hearts so we can reconcile with these others who were here first, these others whose choices shaped the Earth as we know it and made it into the home we know, the only home in the universe where we belong. As Chris said, “They want us to remember what it’s like to be part of the wider world.”

Then Robin stepped to the podium, and she began with gratitude.

So I’d ask [she said] that we all cast our minds back to this morning when we first put our feet on [Mother Earth]. To remember that we had everything that was given us by Mother Earth, by our relatives. We had that first breath of morning air. We had a drink of cool water, we had food, we had the companionship of one another and of crows in the trees and of oak leaves around us. Everything that we need given to us, and our first responsibility is to pay attention to all of those gifts, and to give gratitude for them.

Robin introduced herself by introducing her homeland: the Maple Nation in the Northeast, the lands around the Great Lakes. It’s a place, she said, where two nations who spoke different languages and told different stories had to figure out how to live side by side. “Long before settlers ever came here,” she told us, “we had to agree how it is that we are going to live together—of two different cultures!—in this same place.”

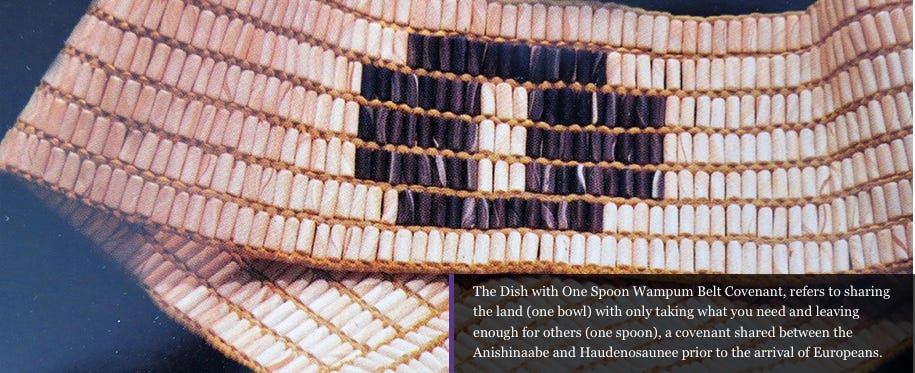

She pointed overhead to a slide with a picture of a belt sewn with wampum, tiny shell beads that are woven into a story. On this particular belt the beads document the treaty that these two cultures finally agreed to. She pointed out the design: purple beads in the center of a white background, the purple beads woven into the shape of a birch bark dish, an onaagan. She explained that these lands in the Northeast were known as the “Dish with One Spoon” territory.

What this signifies [she said] is that our two nations are all fed from the same dish, the same dish that Mother Earth fills for us. And that as two separate nations, we have the responsibility to keep that dish clean and to keep [it] full. So this is an international treaty among our peoples for care of Mother Earth.

She pointed to the middle of the dish:

Also please notice that in the middle of that onaagan is the emikwaan, the spoon [she said], and it’s bezhig emikwaan. It’s one spoon. Think about it [she said]. Two nations. One spoon. This is a statement about justice, isn’t it? This is a statement about sharing.

So, in long-ago times these separate nations figured out that only by taking care of the Earth who is filling their dish can everyone have enough. And only by taking care of each other—because they eat with the same spoon—can they live in peace.

Then Robin got a twinkle in her eye and said, “So of course, you've all studied this in your environmental studies class, right?” And when the auditorium of students and professors laughed, she reflected on why this historic treaty that guided separate nations into peace is not in our textbooks and on our syllabi. It’s because of the erasure of Indigenous knowledge or, she added, “the attempted erasure, because we are still here.”

So she set the theme for the night: how Indigenous understandings of what she called our “shared responsibility for Mother Earth” can help us heal our relationship with the land. “What does the Earth ask of us?” she asked.

Indigenous teachings have much to offer in answering this question because to Indigenous people, the land means something completely different than it means in the current system. And Robin named the differences. Our current economy encourages us to take more and more from the land because in this worldview land is property, and once you take ownership of land, you are in control of it. “You could take care of it,” she said, “or you could wreck it. Doesn’t matter. It’s yours!”

But she grew up with a completely different understanding. Before she went to college she was used to regarding the trees and the flowers and the animals and grasses with respect and love and affection, as members of her own family. To Indigenous people, she said, land is not “resources,” it is “relatives.” To Indigenous people, she said, land is a teacher, where you go to “learn from” not “learn about.” Land is a “healer,” she explained, a “source of medicine, both physical and spiritual, because the land is enspirited.” And perhaps most important is that for Indigenous people land is not a place where you claim your rights to control. Land is instead “the place where we accept the moral responsibility for our relatives.”

Her work throughout her life, Robin said, has been moving between these two very different ways of understanding land. So now she calls for “two-eyed seeing.”

What would happen [she asked] if we had true stereoscopic vision, looking at the world through the Indigenous worldview as well as through the Western scientific worldview? Would we be better equipped to care for [Mother Earth], if we had both of these ways of knowing? I think that we would [she said].

The evidence backs her up. She cited the 2019 UN study that shows that in Indigenous lands, the loss of biodiversity is the lowest in the world. She quoted the astounding statistic from the World Bank: “Eighty percent of the world’s remaining biodiversity is in Indigenous homelands.”

And the reason Indigenous people are such excellent stewards of the land is because the people hold this ethic of care and responsibility for the land. Indigenous people identify with the land, she said. They know “that the people can’t be well unless the land is well.” They know “that we are more than consumers, that we are givers to the land as well.” Values like these add up to healthy land, land that is rich in biodiversity.

So if diversity is good for bioregions, she said, “it’s true for knowledge as well.” “What if Indigenous knowledge could be a guide and a partner to Western science so that they could grow together?” she asked.

And here we came to what for me was the heart of her talk: the contrast between Indigenous and Western forms of science. In the Western academy we study knowledge for knowledge’ sake, she said, so knowledge is “unconstrained by responsibility.” But in Indigenous science, she said, “you have to be accountable to the consequences of the knowledge; you have to think about responsibility and respect and reciprocity.”

So she suggested that these principles from Indigenous thought could guide Western science. So I’d like to take a little closer look at these three—responsibility, respect, and reciprocity—and expand a little bit on them beyond what Robin shared. Because I’d like us to think together about what it means that these values are absent from Western knowing, and what it says about the knowledge system that is right now guiding the whole world.

So let’s look first at the principle of responsibility. In a Western framework, we imagine that knowledge can float free of consequences. And this allows us to ignore ethical responsibility for how our knowing affects others. Care for others, including care for the Earth, is not intrinsic to Western science. Love is allowed to be an afterthought. It may follow inquiry, but it does not guide it.

The idea of knowledge for its own sake is, as Robin says, a “hallmark of Western knowing,” and it arose in early modern Europe to set science free from all limiting belief systems. The founders of modern science wanted to arrive at knowing about the world that is true no matter where you are or who you are or what religious beliefs you hold. They thought that knowledge could be value free.

But four or five hundred years later it becomes clear that knowledge is never value free. Like pure objectivity, value-free knowing is a mirage, because all knowing has a perspective. It always comes from somewhere. It is always embedded in a body; it is always enmeshed in a web of relationships.

And it’s no accident that the idea of knowing for its own sake took hold at the very same time as colonialism and slavery—because ignoring the consequences of our knowing goes right along with ignoring ethical care and responsibility toward others. Many people aren’t aware that there were deep ties between the founders of modern science and the transatlantic slave trade. Prominent scientists in the 1600s and 1700s, members of the Royal Society of London, were also heavy investors in slaveholding companies.

Knowing always has consequences. The question is not whether our knowing or our science has values; the question is which values it will have.

Indigenous worldviews, by contrast, begin with full awareness of this web of relationships, and Indigenous people frame all their knowing within this responsibility to treat others ethically. It’s a logical outcome of regarding all other beings as relatives rather than things. When the world is made of subjects not objects, every interaction is part of a two-way relationship; everything happens between persons, not things.

“Relationships do not merely shape reality, they are reality,” writes Shawn Wilson of the Opaskwayak Cree of northern Manitoba. If the world is made of relationships, then our knowing always affects someone—what the knowing consists of, how we gain it, how we share it. One question Shawn suggests always needs to be asked is, “What will this knowledge be used for?” When this question guides the research, there can be what Robin Wall Kimmerer called “accountability for our knowledge” so that we use it “in a good way.”

So, second, the principle of respect. In a Western framework, there are strict ethical guidelines for how researchers may treat other human beings. But those guidelines are very different in relation to other-than-human beings. We all know there are millions of animals being used for biomedical testing, and the guidelines say they may be made to suffer if researchers believe it will benefit human welfare. In biology research, killing and dissecting an organism is often the final stage of gathering the data.

But if respect were a founding value of every research process, we would have to challenge the idea that as human beings we are entitled to use animals as means for our own ends. We would need to respect their welfare on a par with our own, as is now the standard in research that involves human participants. When respect guides our thinking, as Robin said, we can know that “we are all related, and we are in kinship relationships with one another. No one is more important than the others.”

And if we can take our place in that circle of kinship, instead of thinking we sit on top of the world, we can learn, as Robin says, not just about other beings but from them. Our neighbors and relatives on Earth can become our teachers and guides. When respect guides our science and our knowing, we can become better neighbors and relatives to them.

And finally, the principle of reciprocity. Robin had a lot to say about this one. She told a story she learned from Carol Crowe, an Algonquin biologist, who went to her tribal council to ask permission to attend a sustainability meeting. So the elders asked her what sustainability is, and she sort of laughed and said, “Well, that’s the way our people have lived well on our homeland since time immemorial.” But then she also gave them the Western definitions, which talk about things like promoting sustainable economic growth and continuing to satisfy human needs and maintaining the “resources [of the Earth] so they continue to provide benefits.” But by now she saw that her elders were scowling at her, and she thought they would tell her not to go to the meeting. But they said, “Yeah, you go. You go to that meeting and carry [our] message. That sustainability? That sounds to [us] like they’re just trying to find a way to keep on taking.”

The tribal council saw it for real, didn’t they? We’re managing the Earth so we can keep on taking. I once heard another Native philosopher, Daniel Wildcat of the Muscogee Nation of Oklahoma, call it “the ATM model of family—you know, the relatives who only show up when they need something, to withdraw funds.” He said that’s the kind of relationship we’ve been practicing with the Earth. “We’ve been making a lot of withdrawals in the last two hundred years,” he said, “and haven’t put much back.”

Carol Crowe’s Algonquin elders told her, “It’s not our right to keep taking. When your feet hit the ground in the morning, we should be thinking, What can we give?”

So Robin offered a lot of thoughts on what giving back to the Earth looks like. “Gratitude comes first,” she said.

Other beings are not below us [she added], they are not our property, they are not natural resources or commodities, they are our relatives. They are more-than-human relatives to whom we owe a debt of gratitude and justice.

And there are many other ways to give back. We can take care of the land by helping to restore it. We can work for better environmental policies. We can raise good children, and on and on.

And the one way that is available to every person at every stage of life is to offer our own gifts to others. Robin suggested, to this university crowd, a new definition of an educated person: not someone with a degree but someone “who knows what their gifts are and how to give them in the world.”

Are you an artist? [she asked]. Are you a storyteller? Are you a policy maker? Are you an agitator? What's your gift, and how will you give it? What does the earth ask of us? [she repeated]. I think the earth asks us to change.

And as I’m listening to Robin, I’m thinking about how these principles of responsibility, respect, and reciprocity actually add up to something pretty simple: they add up to love. Because at the dawn of Western science four hundred years ago, when the founders wanted science to be value free, what they took out of the equation was love. Take away values in knowledge—in science—and you take away warmth and affection and care. And when “learning” means something different than “loving,” people may grow rich in learning but impoverished in spirit.

The choice to remove values from knowledge was a chilly one. It means knowing can proceed free of care for others. This isn’t value free, it’s just cold. Because to refrain from cultivating love is not neutral; it actively subtracts warmth from the knowing process. It raises up people, a world-system of people, who believe we can master the facts of the world without considering the welfare of others. It raises up, in a word, masters—people, in a system, seeking to remain on top instead of taking our place as good neighbors and good relatives alongside our more-than-human kin.

Robin summed it up this way: “It seems to me that the crises that we face as a people,” she said, “in a sense boil down to the fact that we haven’t loved the Earth enough.” She wrote her first book about mosses, she explained, because “mosses are so little and no one pays attention to them. I set myself [this] challenge: if I could get people to fall in love with mosses, what else is possible?”

So, what does the Earth ask of us? In a word, more love. More care for our relatives on Earth. So here’s to falling in love with the smallest faces of Earth. Here’s to showing respect for the neighbors and kin, including the unlikely ones, the ones we may not enjoy very much. Here’s to cultivating love in all our relations—with other humans, with other beings. Because each being, each of us, is a face of Earth, and of us has gifts to offer. And if each of us offers our own gifts, what else might be possible?

If you enjoyed this post, don’t forget to hit the LIKE button! Sharing with your friends is great and much appreciated. What does Robin’s talk spark for you? Let us know in the comments!

For digging deeper

For more on the wampum belt that documents the treaty among nations of the Northeast, see “Dish with One Spoon Wampum Belt,” from the Anishinaabek Nation, narrated by Bomgiizhik (Isaac Murdoch) of the Serpent River First Nation people of the Ojibwe. Video with transcript.

To transcribe the Anishinaabek words, I consulted “The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary,” an online resource developed in the Department of American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota. Searchable in both Ojibwe and English.

For more on biodiversity in Indigenous lands, see “Indigenous and Local Knowledge in IPBES,” from the 2019 United Nations Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

The often-quoted stat that 80 percent of biodiversity is housed in Indigenous-held lands comes from a 2008 study from the World Bank, “The Role of Indigenous Peoples in Biodiversity Conservation: The Natural but Often Forgotten Partners,” by Claudia Sobrevila.

I learned many decades ago from feminist theory that value-free knowing and pure objectivity are fictions, and one essay by Donna Haraway was especially influential: “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (Autumn 1988): 575–99. Contemporary postcolonial theorists continue to use this essay; see, for example, sociologist Ramón Grosfoguel, “The Structure of Knowledge in Westernized Universities: Epistemic Racism/Sexism and the Four Genocides/Epistemicides of the Long 16th Century,” Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 11, no. 1 (Fall 2013): 73–90.

For the connections between the Royal Society of London and the slave trade, see M. Govier, “The Royal Society, Slave Trade, and the Island of Jamaica, 1660–1700,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 53 (1999): 203–17.

Shawn Wilson (Opaskwayak Cree) from northern Manitoba, Canada, lives on Bundjalung land on the east coast of Australia and teaches at the Southern Cross University. He wrote a short and powerful book where he reflected on how to do research from an Indigenous point of view. The jacket copy alone is moving: “Relationships don’t just shape Indigenous reality, they are our reality. Indigenous researchers develop relationships with ideas in order to achieve enlightenment in the ceremony that is Indigenous research. Indigenous research is the ceremony of maintaining accountability to these relationships.” See Research Is Ceremony (Halifax & Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2008); quotes are from pp. 7, 34.

For a brief summary of ethics in using animals for biomedical research, see “Ethics of Animal Use” at the University of Connecticut webpage.

Share this post